Dad was a methodical person. He rarely enjoyed the thrill of improvisation. What could have been seen as a preference was definitely an imposition from his dread of the worst imaginable consequences from everything he did. Without his methodical approach to everything he did, he’d quickly sink in anxiety. Of the crippling kind.

I did inherit his tendency to collect whatever irrational thoughts were delineated by that unfightable anxiety. The anxiety that grew in stagnant invisible walls between universes.

“Oh... many years ago, I had a few collections. I remember the stamps from Italy. Your great-grandfather didn't write often, so I asked him to put as many stamps as he could in the envelope. I couldn’t rely on the marked stamps of his very few letters... There’s something about collecting stuff... this way, life can be managed, and you keep things from decaying.”

He had built a few collections in his life, that he cherished: Coca-Cola memorabilia, stamps from Italy, jars of soil and sand from around the world: from the Balearic Islands, to the Chihuahan desert. He enjoyed organizing his collections, labeling, and ensuring the preservation of the items —regardless of their real value. Often low.

In the last months, he had ramped up the hobby, to a degree in which became obsession. I believe it was his way to feel that he hadn't lost control.

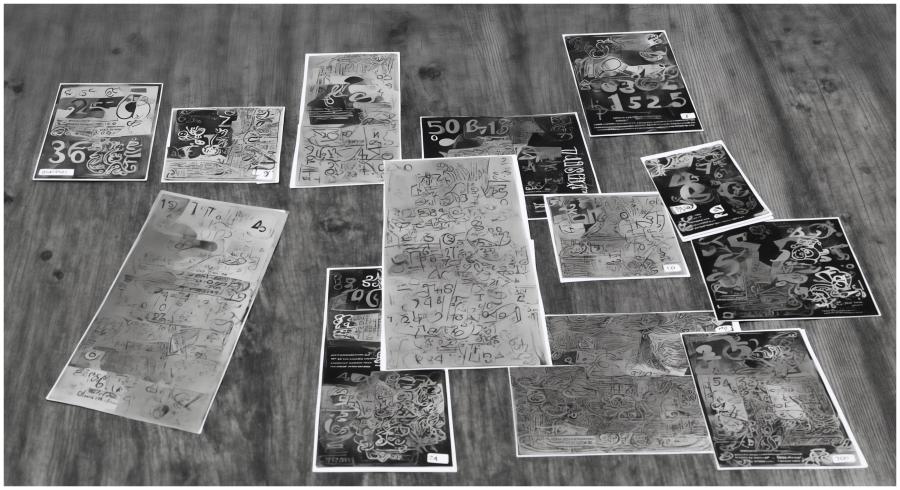

Perhaps he started his most symbolic collection several weeks before he disappeared. He started finding and buying scratch cards. Not the baseball ones, but lottery. He scored some vintage cards, but he mostly collected the ones sold at the convenience store.

It was a very small collection —most lotologists would frown at it. He was extremely picky about which ones were meant to enter the collection, and during those days, sometimes he discarded cards. I couldn’t put my finger on what were the defining variables, on what the hell was he looking for.

Satsuki, when he told her about his last bids and purchases, considered that his behavior was somewhat unexpected: he never had been much of a gambler. In her mind, those cards were a gambler's ordeal. Of course, she wouldn’t even consider that the gambling aspect was completely irrelevant: that he wasn’t intending to ever scratch them.

She wouldn’t have cared about that, though. At that point, she had already downgraded her consideration of Ted to being a childish figure, specially after his behavioral changes. She had been years considering his hobby of collecting petty and juvenile —and generally, she didn’t have any respect left for Ted and saw him with certain condescension. The ensuing issue was that her treatment towards people who were below her baseline respect wasn’t nice. Somehow her baseline had moved.

However, her reaction to that last collection was very different. Something new had limited her expression of hostility towards Ted. Satsuki had always wanted to have a very pragmatic view on things, as if she had a very defined goal. For the rest of us, trying to infer the details of her goal had always been futile. Not knowing someone's goal makes it harder to infer the obstacles they face. Her goal wasn’t happiness —but it wasn’t success either, unless it was an extremely capricious vision of success. It seemed as if her goal in life was merely to pretend that she had a commendable —yet mysterious— goal in life.

Getting to know Satsuki —even for her family— had three stages: at first, the charade she put worked well enough to deceive you into describing her as a socially warm, empathetic and caring person.

If she had no lasting interest in you, she’d lower her guard after certain exposure. Then you’d start seeing traits in her that would shift that description towards cold, calculating and devious.

At a third stage, the truth is that —as your exposure to her tends to infinity— you wouldn’t be able to understand what her ultimate aspiration was. She wasn’t as smart as —I guess— she appeared in the first impression.

She definitely wasn’t dumb, but seemed to have a set of ever-shifting ambitions that allowed her to justify what was ultimately a profound lack of empathy. It wasn’t all bad, though. She wasn’t violent. That time doesn't count. She didn’t have an obvious ego nor struggled for direct adoration. She just seemed permanently bored, her life consisting in constantly reviewing theoretical ways to seek any kind of fulfillment, being that family wasn’t one. Ultimately, she wouldn’t really find any —even with the advantage of not giving a fuck about anyone.

And she struggled not to give a fuck about that collection. I could feel that, even at that age. But that collection had a strange power over her. The collection was able to judge her, to signal that her husband will be removed from her life as punishment for her egoism.

The truth is that her uncommitted pursuit of happiness hadn’t typically interfered with Ted. She didn’t care about his stupid feelings, nor his stupid hobbies and whatever the hell did they possibly meant. And he didn’t stand a fight, so there usually wasn’t any need for confrontation. At the same time, she didn't beat him down. He provided her bits of happiness, yet she wasn't thankful.

I did care about my dad. Although I couldn’t imagine what —if anything— was he willing to express by collecting scratch cards.

Dad didn't have any dreams of becoming a millionaire. The fact that he never scratched any of those cards invalidated that option. He only scratched the cards he removed from the collection, sometimes long after they were no longer valid. To his merit, he never had an unclaimable prize: the discarded ones were always duds, blanks. I think that this fact served his biases, reinforcing his beliefs that the ones he kept were truly valuable in some obscure ways. A value he would never unveil.

No... it wasn’t a collection of hope: most of the cards were irrevocably going to expire. He considered them unique, and not for their potential prizes. If anything, he probably got something out of drowning the hope marketed by these novelty cards into inaction. Maybe it was a way to project what he thought his life had become: still and ready to expire and lose its hidden value. Which was probably “not much”.

It could be that he was hoping to communicate that: to disregard the extreme severity of improbable events —the unlikelihood of a big prize, and the negativity of its aftermath. It was Ted giving no importance to what wasn’t predictable, to what he feared. To the counted accidents that radically change our lives. To the pegs on that fucking bean machine.

As much as I could love Ted, I couldn’t but to be offended by his passivity —to take it as a way of showing how little I meant for him. On the other hand, it wasn’t about me. Nor about Satsuki, who had already made sure that he felt like he deserved nothing in that respect: he wasn’t entitled to affect anyone’s life in any way.

Slowly denigrating him was her strange way to shield me from actually having meaningful interactions with my father, effectively making him a second degree family member —an uncle… further, a stranger. With many small gestures, he would permeate those barriers and connect with me in ways that an eight year old me would convert into a collection of fond —yet blurred— memories.

He would drive hundreds of miles to get different scratch cards. Probably to get away from his wife as well. Maybe he did something else when he was away. Maybe he had a life after all —maybe he had a family where he found himself alive, at home. Unlike the ghosted role he had as my father.

It might sound strange, but I really wish that that was the case. To imagine Ted as a real person, happily in charge of his fate and of its alternative family, makes me happy.

And when he disappeared, I wished he had taken me with him. I always wished that. And that we went back to join his family in a warm place. My real family. The one I never knew.